Usually I

like to cook, but the other day I home late and was too lazy to go to the store. Luckily my neighborhood offers plenty of take-out options; I ordered out from a Chinese

place down the street. I had never eaten

there, but it’s usually pretty busy whenever I walk by. The Yelp reviews said it

specialized in something called “meatless chicken.” It was the most popular thing on the menu.

I ordered

the so-called meatless chicken, along with lo mein and an order of pot-stickers. But when the order arrived and I swallowed a

forkful, I found the dish a little suspicious. The meatless chicken tasted unmistakably

chicken-y – that part they got right. It

was chopped up into small cubes and the texture felt a little spongy, spongy

enough to pass as tofu. But it felt firm

enough to also pass as chicken, chicken so heartlessly raised and artificially

processed, I worried, that it barely qualified as chicken at all. Could the restaurant have made a mistake?

|

| #meatlesschicken #hautgout #deepfriedgoodness |

The

only way to find out for certain was to order the meatless chicken again,

which I decided to do for lunch today. (Note to self: they have a great lunch special.) This time I was relieved

to experience the same type of meatless meat I had ordered the first time. I now believed myself to

like meatless chicken. The texture felt

more assuredly tofu-like, and the flavor somehow less artificial.

Why

was meatless chicken considered such a delicacy at this place? Yelpers called

it a “specialty” that “brings me back to my childhood,” and “the best fake meat

I ever had.” The glowing reviews made

clear that the appeal of meatless chicken also depended on a combination of appearance,

taste, and texture: “tasty fried, slightly chewy goodness!” A combination of sensory and social qualities made

meatless chicken an acquired taste.

What

conditions must be satisfied in order to transport a food from the realm of the

disgusting to the delicious? Our

enjoyment of food has little to do with just one taste or one texture, but

food’s ability to conform to our expectations of what it ought to taste like. Confirmation

of the chicken’s meatlessness exhorted me to re-evaluate my former sensory

observations.

Has

this always been the case?[1] As some readers might know, I have been

working on a history of food connoisseurship during the 18th

century, and I often find myself struck by the passionate responses that new edible delicacies aroused. Take, for example, the dawn of the 18th

century, when well-to-do tables were invaded by French styles of cooking.[2] The English found French cuisine distinctive

for the culinary artistry that went into making rich cullises, dainty poupetons,

the fricassees and ragouts.

The flavors of these new dishes were considered so strong, so peculiar

and so indescribable that a new word entered the English lexicon to describe

them: they had haut-gout.

|

| Most French cooks working in Britain were male, but this was the best picture I could find! |

What

was haut-gout? Well, it’s hard to say. While the OED traces it back to 1645, using

it in the same phrase as a “pickant sawce,”

haut-gout wasn’t exactly a flavor. You won’t find it in an English cookbok. Even

so, haut-gout connoted rich and highly seasoned properties that could not be

described in words.[3] For example, the pungency of soy sauce –- enthusiastically

described in 1736 as having “the highest gust in the world” –– opened the taste

buds to pleasurable new sensations. Others, such as Jonathan Swift, were more dubious. “If a lump of soot falls into the soup … stir

it well,” he sarcastically advised in Directions

to Servants (1731) “and it will give the soup a high French taste.”[4] Because haut-gout didn’t represent one

particular flavor, what it actually tasted like was anyone’s guess. Tasting “expensive” could adopt a variety of

guises, leading one to confuse it with the all-out revolting.

Smell

also wielded power over the likeability of various foods. In the Comical

Don Quixote (1702) the stench of garlic breath might be so bad as to deal a

man a “double death” yet it added a “curious hautgoust” to one’s dinner. Moreover, smell ensured haut-gout’s ability to invade personal deoderized spaces. “I have some

curious green rabbits,” a fictional French character observed in a

1719 play, “with an haut-gout that may be smelt from the forecastle to the

great cabbin.”[5]

Finally,

haut-gout was closely linked to the new

textures of food. Indeed, English

writers dwelled upon the French sauce

–– viscous, rich and pungent sauce –– that provided each dish a little

something extra. But what kind of meat

swam in the creamy goo? Who was to say

that the meat was what the cook said it was? How do we know it hadn’t spoiled? Sauce

provided a dish a sense of artful mystery, but it also exhorted the diner to

trust in the cook’s expertise and benevolence. (Indeed, it’s no surprise that the saucier

is still the highest paid position in a French kitchen.) Perhaps our cultural ambivalence about sauce

is innate. The famous British

anthropologist Mary Douglas noticed that “polluting” substances are often

sticky or viscous. Halfway between a

solid and a liquid, sauces defy easy classification.

But

coming back to my original question, did we arbitrate between disgust and

delight the same way then as we do now? I have noticed that 18th century ambivalence towards haut-gout often emanated not only from the strange sensations it elicited, but also from fears over

where a new food’s enjoyment could lead.

Eating foods with questionable sauces or smells was believed to have psychologically

addicting properties, inevitably leading connoisseurs to seek out new gustatory thrills. Such an affliction could

cause genteel eaters to consume substances that lacked culture or cultivation

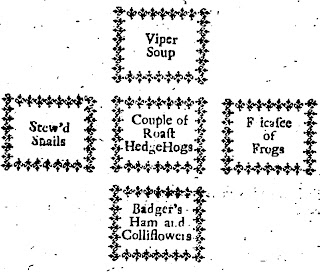

–– substances such as these dishes below. So much for the civilizing process.

|

| This image, as well as the French bill of fare above come from the Universal Journal, or British Gazetteer: April 15, 1727 |

Post-script: By

the way, the meatless chicken was ordered from Big Lantern –– 16th

street and Guerrero. Try it out

sometime!

[1] Over the

past fifty years or so, scholars of various disciplinary backgrounds have

written about

taste and disgust. The experimental

psychologist Paul Rozin has published oodles of articles about preferences and

disgust, famously linking disgust to fears of our animal origins. In his lucid and fascinating book, The Anatomy of Disgust, William Ian

Miller treats disgust as an emotion that organizes the social and moral

universe. I’m still searching for more

work on transforming associations of disgust into associations of taste, so if

you know of any work please let me know!

[2]

The rise of French cuisine has been well documented by scholars. For the culinary changes happening in France,

see Susan Pinkard, A Revolution in Taste:

The Rise of French Cuisine (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

2009). For the reception of French

cookery in Britain, see Gilly Lehman, The

British Housewife and Stephen Mennell, All

Manners of Food: Eating and Taste in England and France from the Middle Ages to

the Present (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1996).

[3] During

the late 17th century, botanists became exceedingly interested in

creating taxonomies of flavor, the most famous of which was devised by F.R.S

Nehemiah Grew. (I’ll talk about him in

an upcoming post.) Yet nowhere in Grew’s

taxonomy or anywhere else does “haut-gout” gain any scientific elaboration.

[4] I’ve

always wondered whether Jonathan Swift got food poisoning from a French

fricassee, for he loved to mock Augustan food fashions. The

Modest Proposal –– which recommended turning Irish babies into culinary

delicacies –– can certainly be read as an indictment of connoisseurial

eating.

[5] Thomas

D’Urfey, The Younger Brother, or the Sham

Marquis (London, 1719).